When my mom was a teenager, she decided she wanted to play in the high school orchestra. She went to the music director and asked if she could join. He said, “What do you play?”

She, bright and chipper, replied, “What do you need?”

He paused, looked at her, and told her they needed a bass player.

“Amazing!” she said. “That’s exactly what I play!”

The man showed her the school’s string bass and said she could take it home to practice. He also told her the names of the strings, pointing to each one as he did. I’m thinking he probably did not entirely buy her story.

As the school year wore on, it got harder and harder to get anything out of that bass. Soon she was sawing like mad and making no sound at all. Finally another bass player (a real one) took pity on her and explained that you have to apply rosin to the bow hair every time you play, so there’s some friction on the strings.

After that semester she left the bass behind and returned to the piano (on which she was actually pretty decent). But she could always say this: for a season, she played string bass.

At about the same time my mother’s bass career was flourishing, my father, a recent immigrant from war-torn Europe, was drafted into the U.S. Army. (This was long before the two met; he was quite a few years older than she.) Not too keen on joining the infantry and being sent to the front lines, he managed to wangle a position in the Army band. There was, he learned, an opening for a piccolo player.

Amazing! as he explained to the presiding officer at his initial conscription meeting. Piccolo was exactly what he played!

“Oh, that reminds me,” said the officer as my father was about to leave. “We just got in a shipment of instruments. Would you like to check out the piccolos?”

My father was in a bit of a tight spot. He could play a very credible violin, and viola, and (unlike his future wife) string bass. He had never in his life played a piccolo. He’d probably never even touched one.

He did, however, play a mean recorder. (He gave lessons to the Von Trapp family, who he reports were not quite as delightful in person as Julie Andrews and her film brood.) Recorder, piccolo … how different could it be?

In fact, the two are as different as driving a stick shift is from riding a skateboard. But he wasn’t in much of a position to quibble.

They walked out back to the newly arrived shipment. The officer opened a crate, pulled out a brand new piccolo, and handed it to my father.

My father took the thing, looked it over, sighted down the bore, tapped a few keys. Kicking the tires, so to speak. Finally, seeing no way to delay further, he put it to his lips, doing his best to imitate every flute player he had ever seen … and managed to get some sort of breathy note out of thing.

Messing with the keys as he blew, he found one note he could trill on, and he did so for a good few seconds with casual expertise.

He then took the terrifying little thing down from his lips (nearly passing out from the expended breath) and gave it the El Exigente thumbs up. And then dashed off to beg a few emergency lessons from a friend (who was principal flutist with the Philadelphia Orchestra) in the two weeks before he had to report for duty.

Alas, his piccolo career didn’t last. Once command realized he spoke German like a native (because he was one), they yanked him from the band, transferred him to Intelligence, and stuck him out in the field as an interpreter. Not only on the front lines, but often ahead of the front lines.

Still, for a season, he did play the piccolo. And quite enjoyed it, too, because its notes cut so sharply through the instrumental texture that he found he could control the tempo of the entire band. If the conductor in him didn’t care for the way the band leader was conducting this particular piece, he could hijack it and mold it more to his taste.

My point in these two stories is not that they happened, but that my parents told them to me, often enough and with so much evident delight that they became an embedded part of how I came to see the world.

In my world — the world according to the stories I heard growing up — you can become whatever you want to become and do whatever you set out to do. From bass to piccolo, the world is your oyster.

When I was thirteen, my mother was taking a group of her middle school students to Greece to perform Aeschylus’ Prometheus Bound, and she needed someone to set the choruses to music. She asked me to do it. Me?! I didn’t see how that was possible. I’d never composed music before. I was only thirteen.

But there was also a little voice inside whispering, “Amazing — composing is exactly what I do!”

So I did.

When I was seventeen I was part of a group of friends who started our own high school. When people hear that story they sometimes say, “You were teenagers! Start your own school? How could you possibly do that!”

Because in the world we lived in, that was not only possible, it was inevitable. Of course, we didn’t know how to go about doing it, any more than my teenage mother knew how to play string bass. But we thought, Start a high school? Amazing — that’s exactly what we do.

So we did.

Now that we’re grownups, it’s up to us all to choose which stories we tell our children — and tell ourselves.

We could tell stories about how unfair the world is. About how mean people can be. How you should be reasonable in your expectations. Or how money doesn’t grow on trees. To me, those stories are no fun, not interesting, and uninspiring.

They are not the fabric of the world I want to live in.

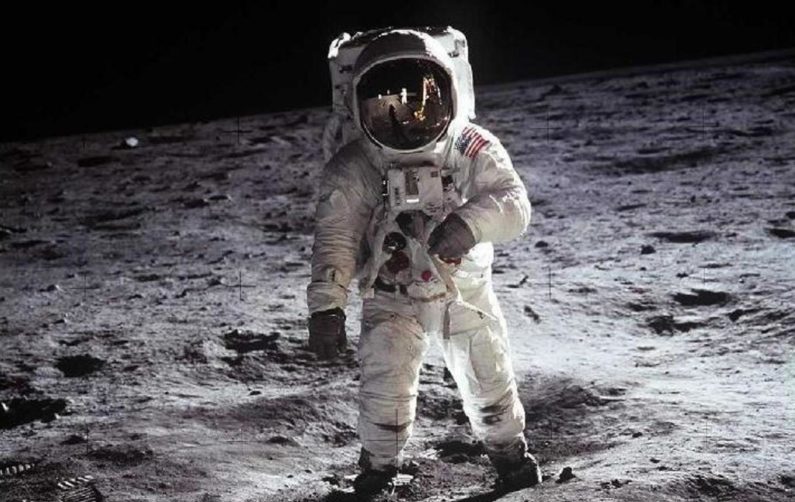

One of my favorite stories is the one about the American president who got up in front of Congress and said we would put a man on the moon, and get him back safely, and do all that within the next ten years.

When JFK made that ridiculous claim (fifty-five years ago last week) we no more knew how to get a man onto the moon than my friends and I knew how to start a high school, or than I knew how to compose music, or than my teenage mother knew how to play string bass. But what did we all collectively say?

“Put a man on the moon? Amazing — why, that’s exactly what we do.”

You’ve probably heard the expression, “Shoot for the moon, and you’ll probably clear the treetops.”

Balderdash.

I say, shoot for the moon — and hit the moon.

And if you don’t know how to start? Find a note you can play, and trill on it.

Masterfully told, young mann!

Hey, thanks big brother! (And thanks for the help in a few of those details!)

Valuable piece of inspiration and encouragement to dealing with challenges in life. “Amazing … that’s exactly what I do!” is worth noting and saying everyday. Thank you.

You are so welcome, Owusu, and thank you — I love the idea of incorporating that phrase in, every day. “Amazing — that’s exactly what I do!”