A few weeks ago, I got a check in the mail for $404.79. But before I tell you what it was for, I have to digress. It has to do with my dad.

My dad was born in Germany and emigrated to the United States during the war. Before leaving his homeland at the age of nineteen, he had published his first book in German: a translation of an eighteenth-century classic text of music composition that had been used by Bach, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and scores of illustrious others. The original text was in Latin; my dad’s translation was, of course, into German.

After arriving here, he was eventually drafted into the American army and shipped overseas, ending up back in Europe as a counterintelligence agent tasked with debriefing citizens. The war’s close found him in a town near the mountain whereupon sat the castle occupied by the legendary composer Richard Strauss (of “Also Sprach Zarathustra” fame — you know, that dramatic music that plays in the opening scene of Stanley Kubrick’s “2001” when the apes discover the big thingamajig).

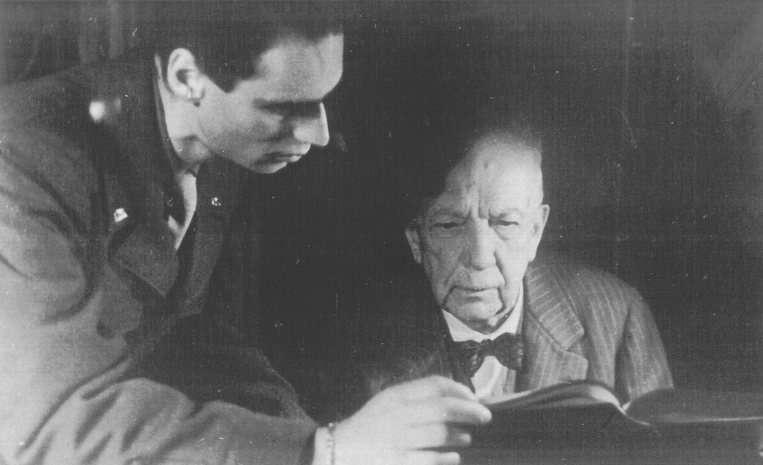

So my dad goes up the mountain to interrogate Strauss, and finds the old man teaching his own grandnephew composition, using … (wait for it) … my dad’s book.

After returning to the States, my dad eventually translated the book again, this time into English, and it was published here by W.W. Norton as The Study of Counterpoint.

My dad taught me composition from it when I was a teenager. It’s still used in schools today.

By now, I’ll bet you’ve figured out how this all ties back in to that $404.79 I just received. If you guessed that the check is from W.W. Norton, you’re right: it represents my portion of this royalty period’s proceeds (a “royalty period” typically being six months) — proceeds from a book my dad began as a teenager in the 1930s and started translating into English before I was even born.

After depositing the check, I went out with my son Chris and bought an LCD monitor he’s been wanting. I doubt very much that my dad ever imagined, when he was nineteen, that someday his efforts would end up paying for a computer monitor for his future twenty-year-old grandson, some years after my dad had himself moved on from this earthly existence — but that’s exactly what happened.

Residual income is like that, and so is love. They both defy the entropy of time.

They last.

(And yes — that really is a photo of my dad and Strauss in the old man’s place on the mountain.)

Thank you for this story. I have known you for almost 30 years now, and after reading this story realize that I actually know very little about your actual history. And now I know at least one more powerful reason why you write books!

My paternal grandfather was a lover of books, something I did not share with him or anyone else until about a week after he passed in 1969. Rummaging around the 10,000-book library in his house, a room I never visited while he was alive, something changed in me, and I have been an avid book lover, reader and writer ever since.

Love is the best residual income there is.

“Love is the best residual income there is.” — Russell Mariani

“Residual income is like that, and so is love. They both defy the entropy of time. They last.” — John David Mann

Great stuff, guys!