In Steve Martin’s online promo for his master class in comedy-writing on Masterclass.com, Martin starts out like this:

I was talking to some students and they were saying things like, “How do I get an agent?” and “Where do I get my head shots?” And I just thought, shouldn’t the first thing you’re thinking about asking be, “How do I be good?”

That is so utterly right on. Except that I would counter by changing just one word:

How do I be better?

I studied for a few years with a wonderful writing teacher in Hollywood, Hal Croasmun, who taught us not only all sorts of writing skills but also an endless stream of career skills and brilliant techniques and tips and tidbits from his a overflowing toolbox. But beyond all that, he told us, if we wanted to pursue a genuinely successful career in Hollywood, there were two fundamental rules we needed to follow.

Rule #2 was, be easy to work with. Because no matter how talented or brilliant you are, if you’re temperamental or a pain in the neck, then nobody cares.

And rule #1? Make your writing excellent.

The thing is, I don’t know how to make my writing excellent. It’s too vast a target to hit, even to know how to aim at. I do know this, though: how to make it a little better.

That’s what Hal taught. And that, I think, is the secret to excellence: constant incremental improvement. Not being perfect, or even striving to be perfect … but to be always perfecting.

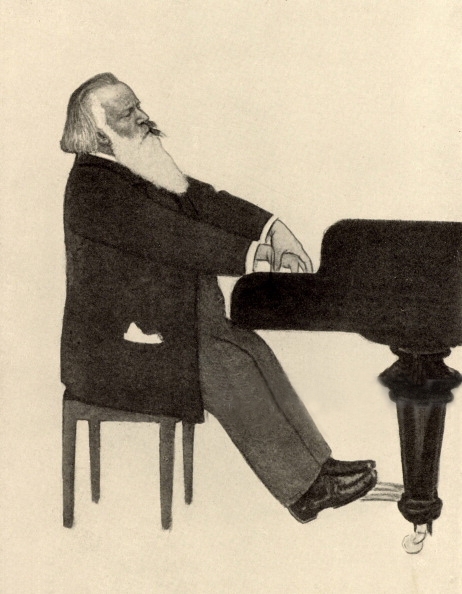

There is a story (probably apochryphal) about Brahms, who was a lifelong acolyte at on the Church of Constant Improvement.

A musicologist, studying the original manuscript of one of Brahms’s symphonies, noticed that one particular oboe passage was written onto a slip of staff paper that had been glued down, on top of the original page. (The five lines of the staff, of course, lovingly drawn by hand.) Utilizing the most delicate of modern technologies, he was able to carefully prize off the single strip and reveal the passage in its earlier, original and slightly different form.

Except that this was not the original. Because this line, too, had been penned onto a freshly pasted strip, laid down over whatever lay beneath. More delicate technology, another revelation: underneath this second strip, there was the oboe passage, slightly different from the other two. And — yes! — this was itself notated onto another hand-cut correction slip.

I don’t recall how many strata the musicologist descended to find the bedrock original, first-draft version of the passage, but I do remember the story’s punch line: it was, note for note, identical to the one on top.

Sometimes it takes a lot of revision to discover the rightness of the original impulse.

I spent years as an editor at several business journals, editing other people’s articles. Most of the contributors were not themselves professional writers, which meant that the quality of the writing coming over the transom was, well, I’ll be kind and say, “varied.” The ideas were often excellent. The execution, not so much.

My job: clean it up. Irons its cuffs, wash off the stains, sew on buttons where needed. Repair rips. Sometimes it meant ripping the whole thing out and sewing it all together again from scratch.

It’s where I learned to write, really. (That’s my #1 piece of advice for people who ask, “How do I get better as a writer? Edit other people’s stuff.)

Most of the time, the original authors did not comment on how their pieces had changed. I often wondered what they thought. (Or if they even noticed!) On rare occasions, a contributor would object. Actually, that’s “on rare occasion,” singular. Happened once. One contributor, whom I’ll call “Jeffrey,” grew incensed when he read my edited version, and demanded we “put it back the way it was.” (We didn’t. Jeffrey was not Brahms.)

Now and then writers would write to thank us for the edits. One gentleman, whom I’ll call “Bob” (because that’s his name), sent us an email thanking us profusely, saying that I had made his stuff a ton better. We started corresponding; I did some editing on one of his books. Later we collaborated on a book. The book we wrote together turned out to be The Go-Giver, which has since sold more than half a million copies. Amazing, the places a little incremental improvement will take you.

Which brings me to the thing I’ve spent the last few hours today, trying to make better. Page one, chapter one, of a new Go-Giver book.

In a recent post I detailed the process of coming up with the story’s opening line. I went through a bunch of duds before arriving at something that deserved to be scrawled onto the page:

Jackson Hill looked like a man waiting to see the executioner.

Only to be fully accurate, that was not quite what I first wrote down. What I first wrote was:

Jackson Hill looked like a man waiting for an appointment with the executioner.

Even before placing the period, I knew this was not quite right yet. It was, as the Duke said to Amadeus, “Too many notes.” I looked at it for another minute, then crossed out “for an appointment with” and replaced it with “to see” — and abracadabra! There it was. The first line.

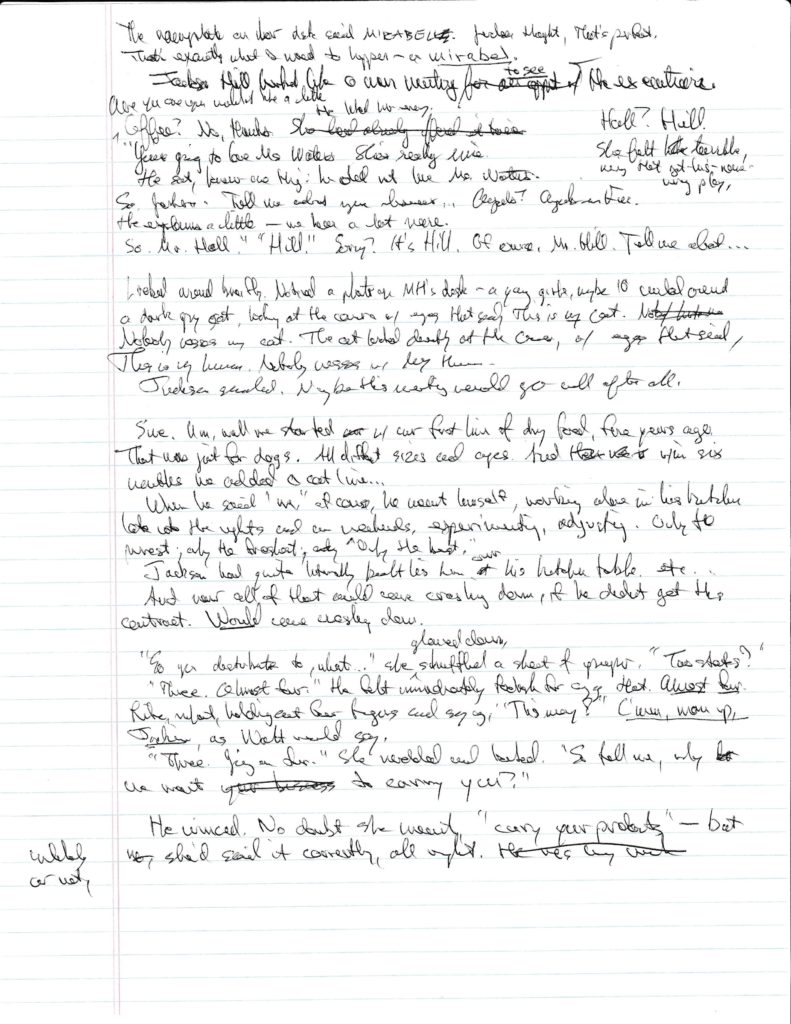

Here’s what that page looks like, complete with all the scribbles that followed:

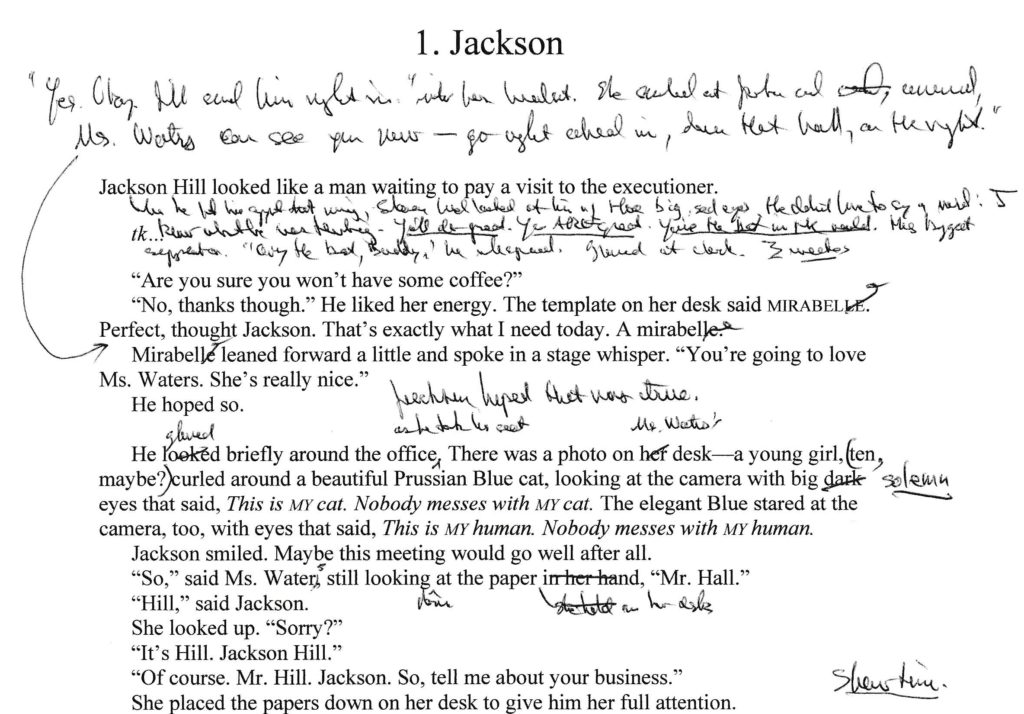

And here, after some more scratching and scribbling and typing and changing and revising, is how the next version looked:

How much of that will end up in the published book, I can’t say. I imagine there will be a lot of little strips of paper laid down, with new oboe lines on them, before we get there.

In another book of mine, The Recipe (coming out this fall — more on that another time), there’s a line I love. I can say that comfortably because this one didn’t come from me, but from my coauthor, Chef Charles Carroll.

“Let me tell you a secret. What inspires me most, every day, isn’t what I already know how to do. A lot of people settle for that. But you can’t become your best that way. Being impressed with what you already know won’t get you to greatness. Not even in the ballpark.

“What inspires me most is what I don’t know. What I can’t do yet. There’s not a lot of juice in being good. You know where there’s a lot of juice? Finding ways to get better.”

Today I am the writer I am, the husband, the father I am. The human being. Tonight I’ll sleep … and tomorrow, I’ll paste down another little handwritten strip of paper.

Photo of Brahms Crosshand at the Piano: This was my #1 favorite piece of art as a child; I asked my parents if they could find me a copy, which they did, and it hung on the wall of my bedroom.

John,

Not only does your writing continue to impress and give me great pleasure,

but it now is being passed on to our grandson, Cam, who is an aspiring writer.

He is about to graduate from UCONN and is writing almost every day having

already completed a novella, a short story, an extensive blog about athletes, and just this month poetry! Do you have advice for this wonderful young man?

Yes! There is a line in the book I haven’t finished writing yet: “We are all superheroes. Most of us just don’t know it.” My advice is just this: the world needs you! Keep reading voraciously, write the very best you can, and then find people who can help you make it better.

My love to you and Ana.

And ours back to you and Skip!

Ha! I just noticed that on the second draft version the original first sentence is left intact, with “paying a visit to…”! Anyone else notice this egregious malediction?