As a kid, Jacob Cohen worked whatever odd jobs he could to help his mom make ends meet. At age 17 he started writing jokes, and within two years he was performing stand-up full-time under the stage name Jack Roy.

It didn’t work out.

After a decade, Jack gave up show business, married a singer named Joyce, moved to New Jersey, and went to work selling aluminum siding. Jack slogged through the next decade, suffering from clinical depression and eventually struggling to rehabilitate his career by night while selling siding by day. His marriage deteriorated; he and his wife divorced, then a few years later remarried again, and finally separated permanently. Not long after this, Joyce died.

End of a sad story. Except…

Except that he did rehabilitate that career.

Jack eventually worked out a new act, based on a new stage persona as a guy who gets rejected no matter what he does. He also took a new stage name to go along with the new bit. He landed a gig on Ed Sullivan, and the audience loved him.

It was his breakthrough. He became a sensation, a success for the rest of his life.

His new name was Rodney Dangerfield.

As great as this story is, to me, this is the part where it really gets good. Because what I love most about Rodney Dangerfield is not how he managed to persevere through all the failure and adversity and finally arrive at his success.

What I love most is what he did with that success.

In the early seventies he opened up a comedy club called Dangerfield’s in New York City, on the Upper East Side, so he could perform and still be close to his kids. (The audience on opening night included Milton Berle, Joan Rivers, Ed McMahon, and David Frost.)

Dangerfield’s was a hit, and Jack (aka Rodney) used it to champion a long list of young and then relatively unknown comedians. People with names like Adam Sandler and Jerry Seinfeld, Tim Allen and Louie Anderson, Roseanne Barr and Rita Rudner, Sam Kinison and Bob Saget.

In the early 1980s he signed up a young (and, again, virtually unknown) comedian to open his act on tour. He thought the young man showed promise. That was Jim Carrey — years before In Living Color, Ace Ventura, and the rest.

Talk with practically any comedian of note over the past four decades, from Leno to Conan, Chris Rock to Jeff Foxworthy, and ask them how they got started, who inspired them, who was critical to the trajectory of their career, and they’ll all tell you the same thing: there was one guy in particular who used his success to help them become successful. Who, instead of being threatened by his colleagues’ achievements, made their achievements his mission.

Here’s what a few of these Dangerfield mentees had to say, upon his death in 2004 at the age of 82:

“Rodney gave you access and made you feel like you were as important. Whenever he came to the club, it made you want to be better.” — Paul Rodriguez

“He would find a place for you if he enjoyed what you did and believed in you. And that was rare. It just shows how generous he was. Most comics are threatened by other funny people.” — Brad Garrett

“I never saw a guy who was so non-threatened that he would just help people.” — Dom Irerra

“The affection felt for Dangerfield when you saw him on TV or in the movies was doubled when you had the pleasure to meet him. He was a hero who lived up to the hype.” — Adam Sandler

“He gave so much to people, he gave people so much joy and so much laughter and so much relief. One of the great experiences in my life is knowing Rodney Dangerfield. I’m so thankful, I’m so thankful.” — Jim Carrey

It took Jack Roy three long decades of heartache, depression, struggle, and repeated failure to reach the far shores of career success, and he nearly drowned many times during the swim across. It was an experience he never forgot — and rather than being embittered by it, he let himself be shaped by those painful years into a person of limitless empathy and compassion.

I’ve written before that loss and failure tend to either deepen your character, or damage it. It really depends on how you use the experience. I love how Dangerfield used his.

Ironically, the man whose trademark line was “I get no respect!” ended up getting more respect from his peers than any other comic of his (or their) generation. He won their respect because he tirelessly gave them his.

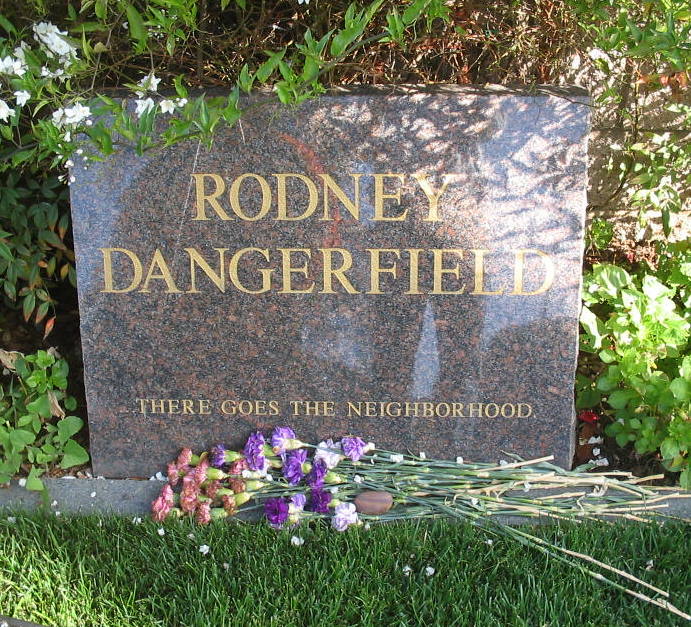

Dangerfield is buried at the Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery, where his headstone reads:

RODNEY DANGERFIELD

… There goes the neighborhood.

I just LOVE that story!

Great story. Always loved Rodney, but never knew the back story. Thank you John David.

John David Mann: as usual, you hit the mark.

Inspirational. Respect given and respect received. Thanks for this. Thank you John David!