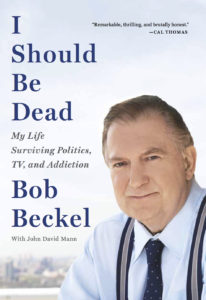

In the photo above, taken circa 1952, you see that boy in the middle? The one who looks so happy and carefree?

He isn’t. He’s terrified.

How do I know this? Because I’ve spent the last year working with him on his story.

People have asked me, what’s it like to write someone’s memoir? My answer: It’s somewhere between being a medium, an actor, and a ventriloquist.

Last month I was asked that same question while being interviewed for an article about memoirs (and the people who write them) for New York magazine. Here’s how my answer came out:

“I think it might be something like what it’s like to be an actor, playing someone’s life story on the screen. … You’ve got to find a place inside yourself that really connects with that person. If you’re going to do a good job at this, you have to get into this person and look at the world through their eyes.”

Looking at the world through that little 7-year-old boy’s eyes has been quite an experience. This is perhaps the most intimate, controversial, and courageous memoir I’ve ever been a part of. It chronicles the life, multiple-times near-death, and ultimate redemption of one Bob Beckel, who survived a painful childhood of alcoholic neglect and abuse only to struggle through most of his adulthood with the demons of addiction and self-destruction.

It just came out today. It is, as one commentator on CNN put it, “A hell of a book.”

Its title: I Should Be Dead.

When you read about his life, you’ll understand why.

Beckel is a veteran of American politics. In Jimmy Carter’s White House he became the youngest-ever Deputy Assistant Secretary of State, then managed Walter Mondale’s 1984 presidential campaign, one of nearly a hundred Beckel-run campaigns over the years.

He is also a veteran of American television. After Mondale lost to Reagan, Beckel went on to a career as analyst and commentator, Crossfire host, stand-in for Larry King, and so on. His behind-the-scenes stories of historic political events, famous television shows and their personalities, are fascinating to hear him tell.

All that is less than half the story, though — much less.

Because Bob is also a veteran of the bottle, the bar, and the battle for survival.

His political and television careers, colorful as they are, take a back seat to the book’s real drama, which is Bob’s terrifying struggle with alcoholism and drug addiction, his effort to be a reliable, effective parent in the midst of crisis and personal chaos, his horrifying crash, and finally his path to recovery, redemption, and a second chance in life.

Here is just one scene, for example, which takes place in the psychiatric ward of George Washington University Hospital, where he has been placed on suicide watch, on the day of George W. Bush’s inauguration:

Last night. How exactly did I wind up in here?

The details start floating back from the haze.

When they wheeled me in here last night (discreetly meeting my ambulance at the rear entrance, VIP treatment all the way), I had a blood alcohol level of approximately a hundred thousand. The ambulance guys had found me that way when they scraped my unconscious body off the asphalt in the back parking lot of some lowlife dive in Maryland. And before that? Think, Beckel. Focus.

I’m at the bar. I’m drunk, maybe drunker than I’ve ever been before. I’m propositioning the woman on the barstool next to me. Turns out she’s married. Turns out her husband is behind me. I swivel around to look.

The guy is sticking a loaded .45 in my face.

Then he pulls the trigger.

How am I not dead?

And that’s before we even get to the opening of Chapter 1.

Beckel is one of the most engaging and colorful people I’ve ever known. Also one of the most loyal, generous, and authentic. And brutally honest.

He has done some terrible things during his life as an addict. He has also done some noble things. He doesn’t apologize about the former, or brag about the latter. No excuses, no evasion, no self-flagellation. He just tells it like it happened. Which is plenty chilling enough.

It was the courage of that honesty, more than anything, that caused me to fall in love with the person and the story when we had our first conversation last summer. One phone conversation — and I could feel that actor-ventriloquist thing kicking in.

Today that 7-year-old boy is a 67-year-old man, and he isn’t terrified anymore. Today he is happy, one of the most serene, contented people I know. But it sure was a hair-raising journey to get from there to here, and it is indeed a miracle that he survived the trip.

Today that 7-year-old boy is a 67-year-old man, and he isn’t terrified anymore. Today he is happy, one of the most serene, contented people I know. But it sure was a hair-raising journey to get from there to here, and it is indeed a miracle that he survived the trip.

Not all of us are alcoholics or drug addicts; not all of us grow up in households simmering with violence and terror. I suspect, though, that if we could peer underneath the surface of the happy photos, we’d discover that every one of us has his or her struggles — our fears, anxieties, guilt, self-incrimination, and destructive impulses.

Our own inner demons.

Fortunately, we also have what Shakespeare and Dickens both called “our better angels.”

Or, as Abraham Lincoln so beautifully put it in his inaugural address, at a time when the nation was being ripped apart by its own inner demons, the better angels of our nature.

If you know anyone who is in recovery from addiction and the darker demons of their nature (and is there anyone who doesn’t know someone who fits that description?), put a copy of this one in their hands.

They’ll thank you.

Congratulations on the new book! My granddaughter just barely escaped from a cycle of addiction following a horrible college trauma. I thank god every day for her recovery.

I am so sorry to hear about this — I wish colleges were safe, but the world is not a safe place. Recovery is a blessed thing!

Bob could have never been able to find a more committed, caring, artful wordsmith to write his beautiful memoir. Congratulations John! I hope the book is a huge success and a NYT bestseller. I wonder what it would take for that to happen for you and Bob?

Thanks, Donna! Answer to question: lotsa people talking about it! (And buying it.)