One week from today my next book comes out. It’s no accident that this happens the day after Memorial Day, because the book itself is a tribute to the memories of eight heroes. But it’s more than that.

When we started working on the book, Brandon and I knew only that we wanted to tell these guys’ stories. We didn’t know exactly how to tie them together, or how that would make a book. As we talked about these friends he’d known, the thread slowly became clear. This wasn’t just a collection of stories about who these men were. It was also the story of how meeting and knowing each one of them changed who Brandon is.

And, our hope is, how knowing them can change who you and I are.

While we were in the process of writing the book, Brandon’s best friend Glen Doherty died in Benghazi. Months later, when we were close to finished, Brandon’s friend Chris Kyle died in Texas. It was eerie … as if the book were writing itself, through the tragedy of real-time events. But in the end, the message of the book isn’t about the tragedy of how these guys left us, it’s about the triumph of what they left us.

Here’s a brief excerpt, from the end of chapter 1. The setting: Brandon’s friend Mike Bearden has died in a training accident, in a free-fall parachute jump in which both main chute and backup chute failed to open. This passage describes the aftermath of that accident.

Mike’s death shook us all up, and I took it hard. It was the first time I’d come face-to-face with the fact that death is an unavoidable part of what we do.

From the vantage point of today, so many years after 9/11, it’s hard to remember what the world was like in July of 2000. In many ways, we in the United States were living in our own bubble. The Cold War had been over for a decade, and in terms of combat, there wasn’t that much going on in the world. We’d lost four guys in Panama in ’89, and had seen more than a dozen of our Spec Ops brothers slain in Mogadishu in ’93, but those tragedies were brief and singular events that already seemed far removed in time. There was a sense of, if not exactly safety, at least relative calm, a sort of age of innocence. Yes, there were occasionally fatal accidents in training, but they were rare. We knew the life of a SEAL was dangerous—at least, we knew it with our heads. But we didn’t really expect to have to deal with the death of a comrade.

I’d been wrong. I’d seen Mike as indestructible. But he wasn’t. None of us were.

When my friends and I were going through BUD/S a few years earlier, one of our instructors sat us down and told us, “Look around, gentlemen. Look at the guys on your left. Now look at the guys on your right. These are your teammates, your friends. And some of them are going to die. You’re going to lose them. That’s the way it is.” Yeah, yeah, I remember thinking, save the lecture, and just let us get our four hours of sleep! At the time his little speech had seemed melodramatic. Now it hit me that what he’d said was the simple truth. They’re your friends. And you’re going to lose them.

What made Mike’s death all the more surreal was that it wasn’t as if he had been killed on the battlefield. It would be easy to decry his loss as senseless. But that wasn’t the truth. Tragic, yes. Wrenching, awful—absolutely. But not senseless.

The training we go through to become the most effective warriors possible is serious. It’s not safe. Mistakes happen, because we’re constantly stretching our limits. If we made the conditions of our training so safe that nobody could get hurt, the training would fail in its purpose. We have an expression in the teams: “The more you sweat in training, the less you bleed in combat.” But it isn’t just sweat. We bleed in training, too. We get pneumonia, break bones, and sometimes worse. The mortal dangers our Spec Ops guys face don’t occur only in the cauldron of political hot spots around the world, but at every step along the way. Special Operations is a dangerous path, and those who tread it are putting everything on the line from day one. Mike died in service of our country’s safety and security—in other words, he died keeping you and your family safe—every bit as much as our friends who would die a few years later in the streets of Ramadi or the mountains of Afghanistan.

Mike died a hero’s death. And we all were left to fight the survivor’s battle: the one with shock, then anger and grief, and finally foreboding, knowing there were more losses to come. Because we all knew that death hadn’t simply paid us a visit. It had come into our midst, staked its tent, taken up permanent residence. From this point on it would be our constant companion.

“You read war books, Clive Cussler and Richard Marcinko, things like that, and you get one kind of picture,” Mike’s dad told me years later. “But there’s a human side to these guys you don’t always read about. These are kids that mothers have brought into this world, and have raised and loved and held dear to their hearts, and you never dream that they’re going to just lay down their lives for somebody else. But it makes you proud, too. They just see it as their job and don’t think twice about it. Because if they didn’t do it, who else would?”

It wasn’t until several years after Mike’s death, long after I’d been through the caves of Afghanistan and back, that I finally had the chance to go through my own military freefall training. Because of a fluke in scheduling, this had been the one piece of standard SEAL schooling that I hadn’t managed to make. I’d been through the basic dope-on-a-rope stuff, but this was different. This was the jump Mike had been doing.

As I sat in that little twin-engine plane, feeling it climb to twelve thousand feet (an altitude sufficient to cause hypoxia if you’re not wearing an oxygen mask) so we could throw ourselves out into the open sky, I felt a twinge of an emotion I wasn’t accustomed to feeling.

Fear.

Mike’s death had touched us all in a deep, dark place we don’t often show or talk about. SEALs don’t scare easily. Part of it is our training, and part of it is just who we are. To a degree every one of us on the teams shares that daredevil gene. But that doesn’t mean we don’t experience fear. We all have our own demons. Some guys have to conquer a fear of the water. In my case, Mike’s death triggered a fear of skydiving, and now that fear was rising up like a dragon.

I told myself this was crazy. I loved flying. Since I was a kid I’d always aspired to become a pilot. I’d trained for this, and never for a moment thought I would have any hesitation when the time came to do it. But there it was.

One classmate saw that plane’s rear ramp door open, sat himself right back down in his sideways-facing seat, and buckled himself in. “I’m done with this shit,” he said, and he refused to jump. I knew how he felt. An expression we have in jump school flitted through my mind: Why would you want to throw yourself out of a perfectly good airplane? Guys say it as a joke to take the edge off the tension of the moment. Right then I wasn’t seeing the humor in it. For a moment, I honestly didn’t know if I could go through with it.

Then I thought about Mike. “What we’re doing here makes a difference,” he’d told his dad. “People need us.” The fall may have killed his body, but I’d never forget that indestructible spirit.

I shook off the fear and jumped.

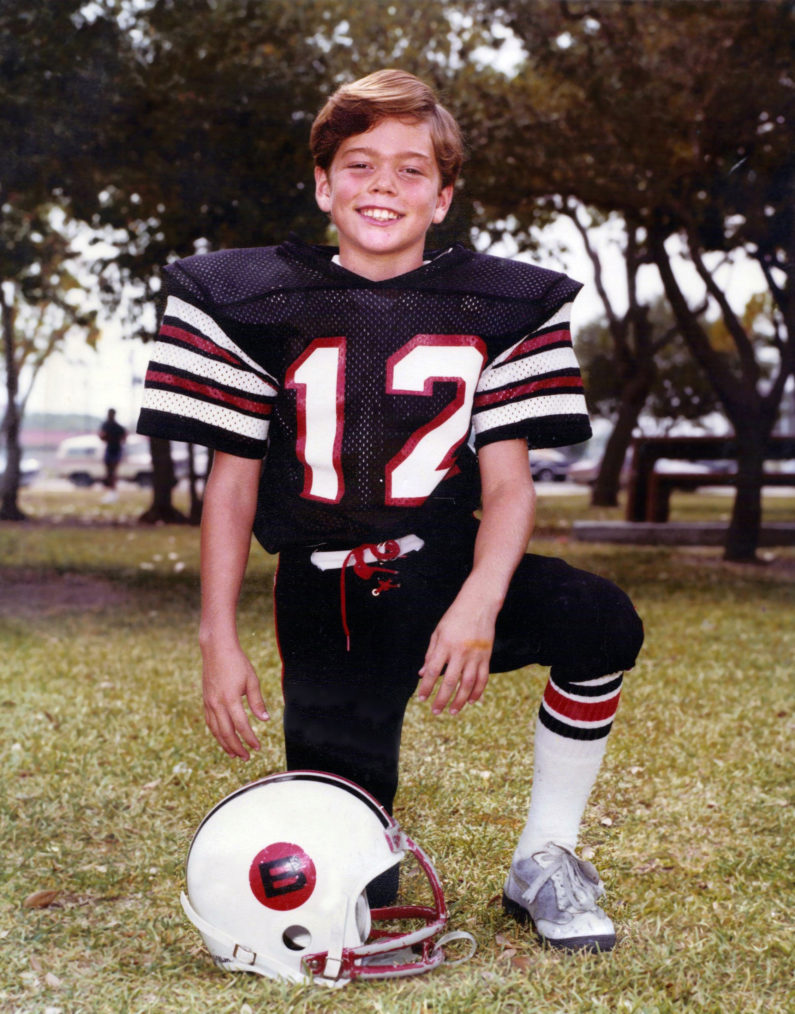

Photo: Mike Bearden, age eight, ready to get in the game, from Among Heroes.